Sorry, I might need to speak up; I’m not sure if you can understand me since the new volume of Mouse Guard melted my face off. Mouse Guard has been one of my favorite comics for a while now—ever since I read a Free Comic Book Day issue, I think—and the newest story arc, Mouse Guard: The Black Axe did not disappoint me for an instant.

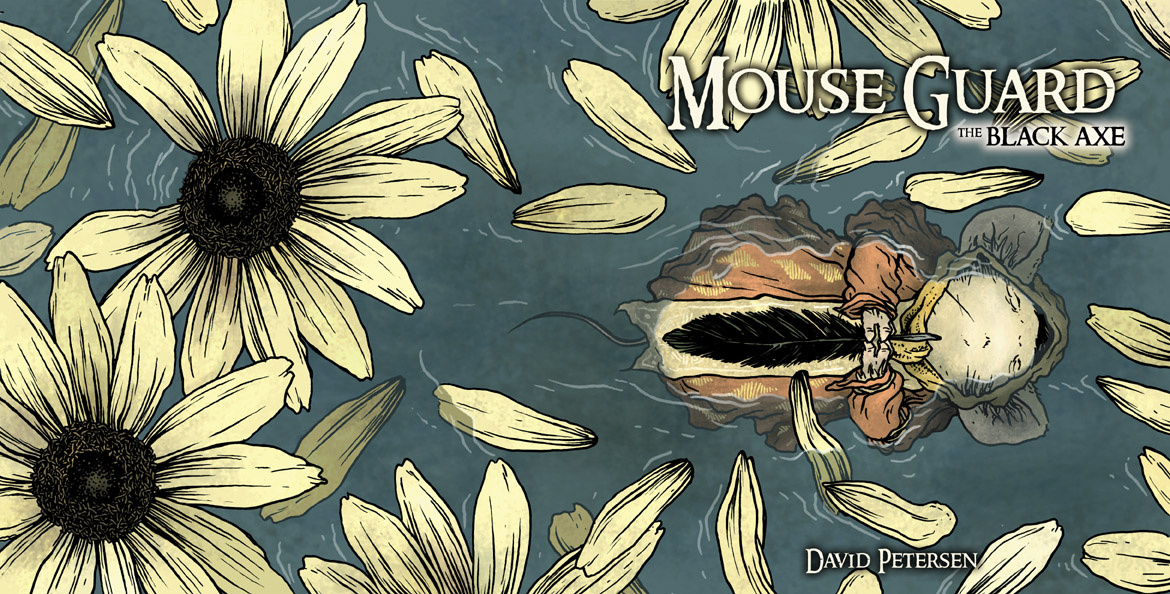

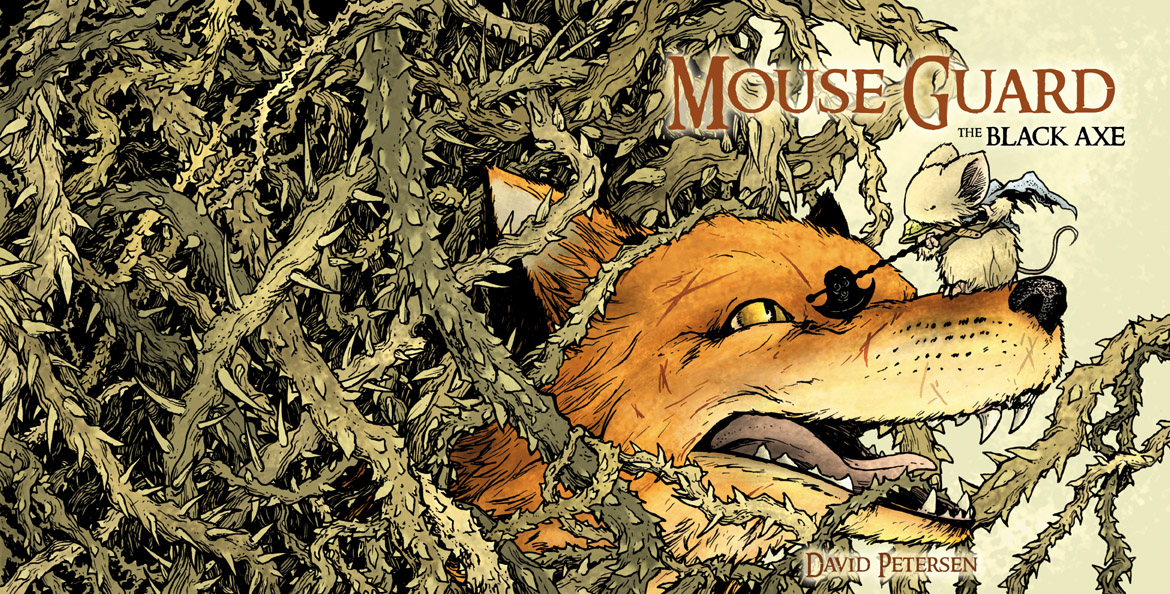

If you aren’t familiar with Mouse Guard, the basic premise is thus: if there was an anthropomorphic mouse kingdom made up of separate quasi-Medieval mouse colonies,who would protect them? The Guard would, that’s who. Well, the guard and the legend—the myth of an immortal warrior, a champion bearing a brutal black axe from which he takes his name, crafted with all the rage and sorrow over the murders of his family that the master smith Farrer could forge into it. The Black Axe! The Black Axe is real, and this is his story. A story of Viking ferrets and Reaver fishers, of heirs and elders, of the death curses of crows and brutal psychological warfare with a fox in a thicket. It is utterly, wonderfully, incredibly awesome. It will make your fingers go m/.

Have you read Watership Down? It was recommended to me by an unlikely source: a friend of mine, 6’8” and looking for all the world like Karl Marx. Well, that is now; I guess back in college he looked more like Morrissey. He ran a pretty brutal Dungeons and Dragons campaign, so when he insisted I read this book about bunny rabbits, I was skeptical. Just seemed out of place—until I read it. Watership Down is a book about heroism, science, exploration, oppression and diaspora—and it is completely hardcore.

The rabbits of Watership Down have a culture, complete with religion, but crucially, they are barely anthropomorphized. They can count: one, two, three, four, a thousand. They aren’t bipedal, they don’t have opposable thumbs or, well, hands at all. They live in holes in the ground: not a hobbit-hole, but a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms with nothing in it to sit down on. You know. Rabbits. Regular rabbits.

Mouse Guard isn’t like that, but I can’t help but see it as being part of the same lineage. The mice live in cities that would make even Bilbo, snug in Bag End, a little jealous. Which is to say, David Petersen’s art is just breathtakingly spectacular. The Black Axe gives us a peek at a variety of locations, from the nautical haven of Port Sumac to the mead hall of the ferret king Luthebon to the fog-haunted briars of a fox’s hunting grounds and to the stained glass lined sanctum sanctorum of the Matriarch of Lockhaven. The big set pieces are jaw-dropping but when you go to pick your mandible up off the floor, take a look at the little details, the background elements and the embellishments.

You’ve probably heard about WETA workshop’s ethos during the Lord of the Rings filming, how they’d add little details like runes or etchings onto their prop pieces, knowing full well that they probably wouldn’t show up on film and if they did, it would probably be too quick for your mind to register it. Well, your conscious mind; the idea being that such careful attention and craftsmanship would create a critical mass of verisimilitude. It worked there, and it works here. Don’t let me go on too long about the scenery, though, because as gorgeous and lush as it is, the characters are at the heart of these stories.

The frame sequence of The Black Axe involves the harsh spring season, where Petersen telling microstories—Guard Mice struggling against adversity, dealing with fierce badgers, tending bee hives, guarding caravans, that sort of thing—with such an economy of panels that Scott McCloud must weep from the beauty of it. Saxon and Kenzie—the fierce over-zealous mouse and the older, wiser mouse, sort of a Raphael and Splinter buddy cop duo—are among the Guard, but their apprentice, the former tenderfoot Lieam, is missing.

That frame story, however, surrounds a flashback that sits snug around the shoulders of Celanawe—pronounced Khel-en-awe, thank you very much—the mouse who will become the Black Axe. He is filled with doubts, filled with bravery; he struggles with questions and loss while always trying to do the honorable thing. Celanawe is not alone; with him comes Em, and with her all the secrets of the Black Axe—or some of the secrets, at least. Friends from earlier volumes of Mouse Guard appear here, as well, in their prime rather than their retirement; Conrad, the salty seadogmouse with his fishhook harpoon, most notably. I mentioned Petersen’s skill at communicating volumes in visual shorthand; each Guard mouse has a visual quirk, a distinctive fur color, a cloak and a signature weapon. A rapier mouse—Reepicheep!—a mace wielding mouse, and so on. Keeping track of the characters is no problem at all.

The sweeping scope of the universe is what takes the cake, ultimately, at least for me; I’m a worldbuilder, by nature. Mouse Guard is not just a well-designed and well-realized world, it is one that makes different choices than the easy one. The best for-instance of what I mean would be the mice’s enemies in the great war: weasels. It would have been easy and expected to go with rats, but making their antagonists Mustelids? That is just genius. Their predatory nature, their sinuous bodies; Mouse Guard started off as a role-playing game, once upon a time, and the weasel family are the orcs and gnolls of the mouse world. In The Black Axe, they even get the treatment I want for orcs in fantasy gaming: they get dealt with as characters, as people. Oh, the fishers that chase Celenawe and Em are wholly terrifying, adorned in the dead flesh of their enemies, but they are contrasted with the ferrets, who are meat-eating and natural enemies of mice—well, natural predators, really—but have honor and hold to it, have feelings and loves and hates.

I mentioned this started as a game—there is Mouse Guard role-playing game now, as well, using a simplified version of Burning Wheel—and the use of mice instead of humans just alters and mutates your suspension of disbelief. Sure, maybe a brave warrior mouse requires more suspension of disbelief than a brave warrior human but once you buy in up-front, you get a lot of interesting stuff on the back-end. Take for instance, one of the pages towards the beginning; we see Guard mice battling a snapping turtle. Think of the scales involved, tiny mice, giant turtle—really terrifying. It is, for all intents and purposes, a dragon. Only, see, instead of your brain needing to grapple with “giant sentient flying magical reptile that breaths fire and loves gold” you get it all wrapped up in a real world package—a snapping turtle. Or an owl, or a snake or—well, you see what I mean. Potent stuff. It’ll melt your face right off.

Mordicai Knode made a Mouse Guard character; he was a former circus-mouse named Arkady, who wore a top hat and carried a whip. Tell him what your Mouse Guard character is or would be on Twitter or find him on Tumblr!